Crain’s Detroit Business

Minnah Arshad

Aug. 26, 2022

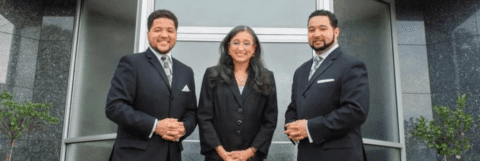

Courtesy of James H. Cole Home for Funerals Inc.

Karla Cole with her sons, Brice and Antonio Green, standing outside the West Grand Boulevard location of James H. Cole Home for Funerals Inc. in 2019.

Fourth-generation funeral home director Antonio Green can still remember watching his grandfather crafting caskets by hand.

These days, the caskets coming into the James H. Cole Home for Funerals are prefabricated and can be made simple or ornate enough to satisfy any customer.

Since its founding more than a century ago, Detroit’s oldest Black-owned funeral home has witnessed leaps in technological advancements, yet the core of the business has remained the same: being there to honor the dead and provide loved ones with peace in a time of grief.

“You just don’t know day-to-day or even year-to-year exactly what’s going to happen,” said Green, whose great-grandfather James H. Cole started the business in 1919. “Everybody’s set the stage well, so it’s just a matter of carrying the torch.”

In the nation’s largest Black-majority city, entrepreneurs of color share a unique perspective on progress over the last century. And as August closes on Black Business Month, entrepreneurs of color in Detroit have been reflecting on a rich history that mirrors the tumultuousness of America’s relationship with race.

Minority-owned businesses, born in many cases out of necessity, have endured unique challenges for decades. When Black communities were turned away from services, they filled voids by building their own institutions, from bars to banks.

And, of course, funeral homes.

“Blacks have always had to bury their own, pretty much,” third-generation President Karla Cole said. “White people would not bury Blacks, so Black funeral homes had to come into existence for that reason.”

Unique challenges

The state’s first African American-owned certified public accounting firm, George Johnson and Co., was founded in 1941 at the height of the Black Bottom neighborhood and nearby Paradise Valley business district. It was a time of flourishing entrepreneurship for the community in — until the government authorized the building of a part of Interstate-75 right in 1959.

Many Black-owned Detroit businesses were leveled and lost, never to be recovered.

Today, data show that entrepreneurs of color still make up a shockingly low portion of the overall number of businesses in Detroit.

A 2021 report from the Federal Reserve Bank of Chicago says 10% of Detroit businesses were Black-owned in 2020, while the Census Bureau found 77.1% of Detroit’s population was Black or African American.

Anthony McCree, chief executive officer and managing partner at George Johnson and Co., said one of the requirements to become an accountant in the mid-1900s was to work for a CPA for a couple of years. But Richard Austin, GJC’s founder, was shut out from fulfilling that requirement; nobody would hire him because he was Black. Eventually, a professor allowed Austin to work for him at night, McCree said, providing him a pathway to certification.

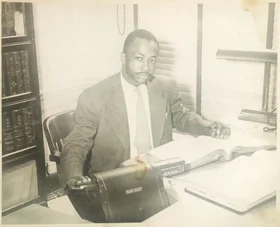

Courtesy of Anthony McCree

Richard Austin founded George Johnson and Company in 1941.

Opening GJC in 1941 was a revolutionary moment for the Black community. It was the first African American-owned CPA firm in Michigan, originating in a Detroit apartment building at the height of Paradise Valley’s existence, McCree said.

Today, it employs about 30 people across three offices in Detroit, Chicago, and Cincinnati. McCree said this was likely the firm’s best year.

Austin’s clientèle included small, Black-owned businesses in Black Bottom that were turned down from CPA services by most other firms. GJC provided a service to the entrepreneurs of the city at a time when no one else would, McCree said.

“Times are different now where the obvious challenges aren’t there that he dealt with, but some of them are,” he said.

While many of the challenges minority accountants faced in the past were by way of explicit discrimination, McCree hinted toward implicit biases that continue today, such as the different level of confidence a client may have in a Black-owned firm.

The Chicago Fed also noted that Black entrepreneurs faced unique challenges when trying to scale up. The report said that 30% of small, Black-owned businesses nationwide were concerned about credit availability during the COVID-19 pandemic, compared to 12% of small, white-owned firms that expressed concern. Barriers to capital were also concerns for Black entrepreneurs before the pandemic, like limited credit history, lack of financial records, and traditional banking relationships, the Chicago Fed stated.

Michigan’s only Black-owned bank, First Independence Bank, was founded in 1970, motivated by the unrest that swept the city in 1967, Chief Executive Officer Kenneth Kelly said. About 22 members of the Black community came together and decided to start a bank to support its community after seeing the financial challenges of business owners without access to banks. The founding members labored for about two and a half years to go through the regulatory process and raise funds, and in May 1970, the bank opened its doors.

Photo Credit: Breann White

Kenneth Kelly is the chief executive officer of First Independence Bank.

Currently, Kelly said, First Independence employs about 70 people and its has about $400 million in assets.

“I think it was the vision of those individuals looking to see that they could make a change in the community by starting and controlling a bank that would be interested in the community they were trying to grow,” Kelly said.

At that time, African Americans struggled to get loans from existing banks, limiting them from becoming homeowners and advancing their businesses. First Independence enabled many people of color to grow financially.

At the same time, Kelly said the opening of First Independence pushed other longstanding banks to hire employees of color in professional jobs.

“Larger banks noticed they had to begin to be a little bit more inclusive to the African American community if they were going to be successful long-term,” Kelly said.

One hurdle the institution continues to face is reaching a customer base beyond communities of color.

“While our banks are Black-owned, they’re not Black only,” Kelly said, emphasizing the importance of a wide customer base for the bank’s long-term success.

The Federal Deposit Insurance Corp. reported a total of 19 Black-owned depository institutions nationwide in the first quarter report of 2022 out of 4,796 total depository institutions.

Changing with the times

Even a business that will always be needed has to change with the times.

“Because the funeral business, the industry, is so slow, we’ve actually had the opportunity to stay ahead of the game and even (be) trendsetters in some ways,” Green from James H. Cole said.

At its newest location on Schaefer Highway, which opened about 12 years ago, the company installed screens in all its visitation rooms so loved ones could play memorial videos, a screen at the front door to see the deceased person’s photo and service information, and a digital board in the lobby to showcase visitations in progress. At the height of the pandemic, livestreaming services also gained popularity.

Due to changing industry regulations and expectations, the company saw peak revenue in the late 1960s and early ’70s. In the early 1980s, profit margins for funeral homes were much higher, at around 15%, Green said. By the early 2000s, it had dropped to less than 10%.

“When times were a lot simpler, you had the ability to profit more than you do even nowadays,” Green said.

However, technological advancements mean the business has more access to a variety of manufacturers, so they’re no longer tied down to one manufacturer and price.

The funeral home declined to disclose revenue information but said it serves about 2,000 families annually. The National Funeral Directors Association said NFDA-member funeral homes serve 113 families per year on average. These numbers were significantly higher during the height of the COVID-19 pandemic, but Cole said the funeral home was relieved to see those numbers drop back.

At First Independence, Kelly said he has prioritized keeping the bank’s technology updated to ensure it remains competitive with other banks across the country.

“To be candid, it’s an investment, which means you really have to make the decision to spend the dollars up front with the intent of knowing it’s going to have a longer-term impact on your business and your customer relationships,” Kelly said.

Courtesy of Anthony McCree

Anthony McCree is chief executive officer and managing partner at George Johnson and Company.

Prioritizing digitization in workflow at George Johnson, especially during the pandemic, has been crucial to the success of the CPA firm, McCree said.

Technology like cloud-based platforms, updated phone systems, online secure file portals and software updates have enabled the company to keep up with larger established firms, McCree said, and ensured a seamless transition to remote working in the last couple of years.

“When the world shut down, we were able to pick up our computers, go home and start working just as if we were in the office,” McCree said. “Our client service didn’t miss a beat.”

Shrinking the racial wealth gap

Kai Bowman, chief operating officer of the Metro Detroit Black Business Alliance, said supporting Black-owned businesses is a crucial step in shrinking the racial wealth gap.

A 2018 study by the W.K. Kellogg Foundation stated that Michigan stood to gain $92 billion in economic output by 2050 if racial disparities in health, education, incarceration, and employment were eliminated.

The study said that by the middle of the century, 40% of Michigan workers will be people of color.

“The racial wealth gap is perhaps one of the biggest economic issues in this country,” Bowman said, accelerated by a centuries-long “headstart” when people of color were barred from property ownership and other economic freedoms.

Even now, entrepreneurs face unique barriers to resources. At the beginning of the pandemic, the Small Business Administration began the Paycheck Protection Program, established by the CARES Act, which provided businesses with funds to sustain payroll and other costs. However, Bowman said early rounds of the program had one caveat: businesses had to demonstrate a banking relationship.

Due to historic racial barriers to financial institutions, Bowman said this was a “nonstarter for a lot of Black-owned businesses.”

MDBBA currently offers capital and technical assistance programs to businesses in Wayne, Oakland, and Macomb counties. It launched last spring with $1 million from TCF Bank and was founded by Charity Dean, who previously led the city’s Civil Rights, Inclusion and Opportunity Department.

“The future has the potential to be extremely bright for Black entrepreneurs — with intentionality and focus on undoing 400 years of systemic barriers that have hampered our community,” said Bowman. “I’m optimistic that with the help of our organization and other partners, that we can continue to amplify the plight of Black businesses and amplify the resources that are available.”