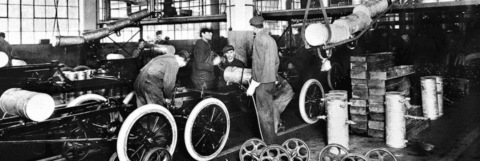

The Diego Rivera Murals at the Detroit Institute of Arts capture a time when it didn’t take much to work in the auto industry. But these days, it requires a lot more than just brawn, even down on the line, where assembly workers increasingly must learn about things like statistical process control.

The auto industry is in the midst of its most radical transformation in more than a century. Whether you’re designing and engineering a vehicle, manufacturing it or marketing and selling it, there’s a good chance you’ll need to learn new skills going forward as automakers migrate from internal combustion to battery-electric propulsion, develop cars connected to the cloud, and shift to online retailing.

Making the transformation work “is all about the talent,” said Ford Chief Executive Officer Jim Farley. And he’s underscored that point since taking the top job with Detroit’s second-largest automaker by reaching outside the industry to fill some critical posts.

In March, Ford brought in Jennifer Waldo, a former Apple exec, to run its human resources operations. Six months earlier, it hired Doug Fields, former head of Apple’s secretive car program to run advanced technology and embedded systems operations.

General Motors and Stellantis have made similar moves to nab top talent from Silicon Valley and other tech centers – as have suppliers and foreign-owned brands, like Hyundai and Toyota, who have major technical operations in the Detroit area.

“The type of skills – and the workers the industry needs – has changed,” said Kristine Coogan, a managing director with consultancy KPMG. “Once, the focus was on mechanical system. But cars are becoming more and more complex. Consider that the Ford F-150 has 150 million lines of (software) code to make it go.”

Indeed, today’s typical vehicle is something of a computer on wheels, often with over 100 separate microprocessors onboard. And that requires a very different skill set at every level, industry insiders agree.

But the shift is disruptive. Ford in July announced up to 8,000 job cuts as it ramps up its electrified Model e unit, while cutting back Ford Blue, focused on traditional gas and diesel-powered products.

The final number could depend on how many of those employees can be retrained, according to Coogan, who added that there will be “a large population of people who need to be reskilled for the jobs of the future.”

There’s little doubt a sizable share of this new talent pool will need to come in from outside. So far this year, GM has hired in more than 7,000 new employees, noted Cyril George, the automaker’s chief talent officer.

A sizable share, as many as “70% to 80%,” said George, have been assigned to areas that might not have existed only a decade or two before, such as the carmaker’s battery-electric vehicle program – GM is planning to launch around 30 battery electric vehicles (BEVs) just by 2025, including the new Cadillac Lyriq and recently unveiled Chevrolet Blazer EV. Others will focus on self-driving technologies, infotainment systems and new marketing and distribution technologies such as CarBravo, the carmaker’s online used car website.

The transformation of the industry is only accelerating, said David Cole, director-emeritus of the Center for Automotive Research. And when it comes to shifting directions on the talent needed to make the “new” industry work, “This is a big deal, and it’s only going to get bigger.”