Detroit Free Press

May 31, 2023

Nancy Kaffer

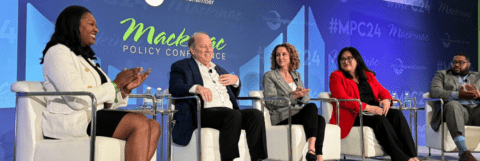

MACKINAC ISLAND — The first panel at this year’s Mackinac Policy Conference, which started yesterday on the northern Michigan island, aimed to discuss “How Employers Can Help Solve Michigan’s Housing Affordability Crisis.” The rest of the conference agenda is dotted with other such subjects: panels on economic equity, affordable childcare, criminal justice reform, equity and childcare — nine, all told.

I’ve covered the Detroit Regional Chamber‘s annual conference since 2009, so trust me when I tell you that this is different. Fourteen years ago, none of these things were on most businesses’ agendas, at the conference or otherwise. Business, for the most part, tried to steer clear of social causes that could alienate customers, preferring instead to use its collective influence on things like tax and regulatory policy (all of which have social impacts, though business likes to pretend otherwise).

Things changed, a little, as it became clear that both young workers and employers needed functional mass transit; public transit became a perennial conference topic, then did investment in pre-K and education, as report after report showed Michigan’s economy and workforce falling behind.

I’m not foolish enough to suggest that hosting or attending a few panel discussions signals a sincere commitment to solutions, but the unmistakable presence of social and racial justice causes at the state’s premiere business policy event is a fascinating insight into our state’s changing political and pragmatic calculus.

“I am a cynic about this, as are most folks, because we have not typically seen business be concerned about what amounts to social justice or social equity issues,” Portia Roberson, CEO of social service agency Focus:HOPE told me last week.

But a lot has changed, she said: “There are corporations that have leaders who feel like it has been time, or beyond time, to support these efforts … but probably some are doing it because they feel they have to, because of demands from the workforce that they participate in this economy and this world in a different way than they used to.”

In a Glengariff Group poll commissioned by the Chamber before the conference, 65.6% of respondents said businesses have a role in the debate over social issues facing Michigan. In December, 59.6% of voters told Glengariff pollsters that a state’s social positions would influence whether they’d take a job in that state.

Social causes have a particular importance to younger workers, Roberson said.

“They are trying to recruit young people into the workforce, and young people want things like social justice movements and work life balance,” Roberson said. “I won’t say they hold all the cards, but they hold a lot of them.”

A set of recent reports have pointed to two demographic trends, said Anika Goss, CEO of think-tank Detroit Future City: Michigan’s population loss and knowledge drain continue. At the same time, the state’s minority population is growing, Goss said, and is expected to increase significantly by 2050.

“Michigan is going to be significant in terms of diversity, in terms of Black, Latino, indigenous and foreign-born residents, and these are the demographics we don’t invest in, and are falling behind in every category: education, economics and health,” Goss said. “I’m not so Pollyanna-ish that I believe companies are like, ‘We need to invest in this diverse population,’ but there are liabilities to the economy when we are not investing in our own talent in Michigan. We are not making major investments in future of work.”

Without that, Goss said, it’s unclear whether Michigan will have a sufficiently educated population to meet employers’ demands.

Accepting the need for higher education remains a challenge in this state. Despite clear evidence that college-educated workers fare better in economic downturns, a March Glengariff poll found that just 26.5% of Michigan voters thought having a college degree was very important; more than half of respondents said college wasn’t worth the money.

“We end up losing this 18-24, college educated demographic. They have a lot of options,” Goss said. “If we’re not offering Michigan as a place where you can afford to live, where you can see yourself staying once you find a partner and have a child and put that child in school, if you don’t see Michigan as a place that values you and whatever it is that you do …”

It’s the same with women. That poll from March found that 6% of female poll respondents had stopped working since the pandemic. For women making less than $25,000, it was 18.2%.

“It’s really significant, women are not working in Michigan (in the same numbers), and we are no longer in a position where we can afford for women not to work,” Goss said. “If we don’t have family care options, this will stunt our ability to grow the economy.”

All of these workers, she said, can find other places to live.