Shattering Misperceptions

May 30, 2015Mike Rowe is on a one-man mission to bring national attention to the importance of skilled trades training across the country. As the former host of Discovery Channel’s hit show “Dirty Jobs,” Rowe spent countless hours traveling to all 50 U.S. states and working more than 300 different jobs, transforming cable television into a landscape of swamps, sewers, ice roads and coal mines. Based on these experiences, Rowe launched the mikeroweWORKS Foundation, which awards scholarships to students pursuing a career in the skilled trades; was featured on a TED Talk; testified before both the U.S. House and Senate; and eagerly speaks to just about anyone who will listen.

Taking his love of skilled trades even further, Rowe launched a new series titled “Somebody’s Gotta Do It” on CNN in 2014, joining innovators, do-gooders and entrepreneurs in their respective undertakings. Rowe recently sat down with the Detroiter to discuss the importance of shattering misperceptions of skilled trades and blue collar jobs in Michigan and the United States.

What sparked your interest as an advocate for the skilled trades?

That’s a long story. I grew up next to my granddad on a little farm in Baltimore, and he was a master electrician, plumber, steamfitter, welder and mechanic — the kind of guy who can build a house without a blueprint. I was always in awe of that talent, but sadly that gene is recessive because I didn’t inherit it at all and ended up in the entertainment industry. By the time “Dirty Jobs” came along, I was in my early 40s and he was fading and I wanted to do a show that looked like work because, at that point he had never seen me do anything on television that could be confused for actual labor. There weren’t many shows on TV either that paid an honest tribute to the jobs my grandfather grew up doing. He only had an eighth grade education, but he was heroic and in the back of my mind I wanted to do a show that tapped into that.

While filming an episode of “Dirty Jobs,” you worked as a bridge maintainer on the Mackinac Bridge. What stood out for you on that job?

So many things. That was a pivotal job. Optically it just looked like something most people have never seen. We did a pretty good job of shooting the episode and capturing the perspective of what those guys do day in and day out. It was also really significant to me because it was the first time a municipality never said “no.” We’re so used to people saying “I’m sorry we can’t let you do that.” As a joke, I was asking all sorts of things that I was sure they would say no to, like would it be OK to go down inside the towers under the water to paint one of those tiny honeycomb coffins and they said “yeah, we’ll let you do that.” At the end of the day, I asked, “What are the odds you will let me walk across that girder and up the suspension cable?” and they said, “Sure. You want to do that?” It was a perfect storm of good things. It was a very appreciative state and a bunch of passionate guys who were eager to show the world what they do to maintain the bridge.

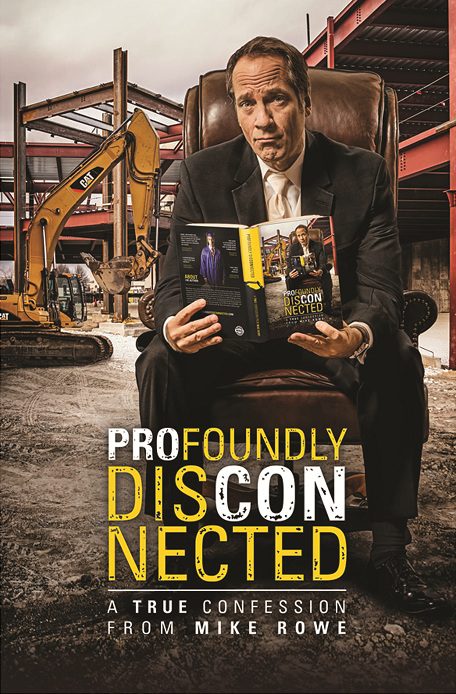

Mike Rowe addresses America’s worsening skills gap and the concerns that follow closely behind in “Profoundly Disconnected.”

The second season of “Somebody’s Gotta Do It” recently premiered on CNN. What sparked your idea for the show? Where do you find inspiration and how do you identify the “innovators, do-gooders, and entrepreneurs” you want to feature?

Ninety percent comes off my Facebook page. “Dirty Jobs” was programmed almost entirely by viewers and so is “Somebody’s Gotta Do It.” It started not just as a tribute to the work in skilled trades, but kind of an homage to people who were passionate about what they do and a little afflicted by their desire to do what they do. When we finished “Dirty Jobs,” I wanted to circle back to my original idea of a broader show about vocation, avocation and passion.

How can we as a nation make technical and manufacturing career pathways more attractive for parents and school counselors?

The short answer is PR. It’s very noisy out there. Everyone has an agenda and crowding into the space to have this conversation about the definition of a good job in 2015. That’s essentially what’s for sale. We get to decide what a good job is and what’s aspirational. The things we do as parents and educators and the messages we send via pop culture are immensely impactful to a kid who is trying to figure out what to do with the rest of his or her life.

Part of the reason so many opportunities in the technical trades and skilled labor feel like a vocational consolation prize is precisely because that’s how we’ve couched them. It’s a very difficult thing to do, but your perception of a plumber, in all likelihood involves a 300-pound guy with a giant butt crack because we’ve seen that over and over again. We’ve heard the best path for most people is a four-year degree. These things become platitudes and before long it’s inculcated in our minds that there is a path to success and this is what it looks like. We have to be mindful that these stereotypes and stigmas actually exist, and rather than pretend they don’t, it’s useful to talk about them head-on.

What needs to be done to reverse misperceptions of skilled trades and blue collar jobs in Michigan and the United States?

There’s this constant balance that goes on between the definition of a good job and our understanding of a truly valuable education. Language matters a lot. We don’t really talk about education today. We talk about higher education and we talk about alternative education. That really informs the conversation because you set the table in a very specific way. The alternatives to higher education feel subordinate simply because the language we’re using to describe them implies a certain primacy to one route.

“There’s no such thing as a mechanic today. You open the hood of your car and you don’t need a mechanic. You need a rocket scientist or a software specialist. We’ve advanced so quickly that we’ve pulled skilled trades into a much more sophisticated career path and the language and perceptions simply have not had time to catch up.”

It goes back to challenging outdated stereotypes. There’s no such thing as a mechanic today. You open the hood of your car and you don’t need a mechanic. You need a rocket scientist or a software specialist. We’ve advanced so quickly that we’ve pulled skilled trades into a much more sophisticated career path and the language and perceptions simply have not had time to catch up. In Michigan there’s something like 100,000 jobs on the books available and maybe 15 to 20 percent require a four-year degree. The others require very specific training and a willingness to roll your sleeves up and work.

The mikeroweWorks Foundation aims to award scholarships to men and women who have demonstrated an interest in and an aptitude for mastering a specific trade. Does any particular success story stand out for you about someone who received help from the Foundation?

Hundreds. We’ve done a little over $3 million in work ethic scholarships. I’ve got more notes, videos and feedback from people than I know what to do with, people who took the time to learn a skill. I got a letter from a kid in Saudi Arabia who ended up going to SkillsUSA a few years ago who is now making $140,000 a year welding. He was previously living in a trailer somewhere in Kentucky taking care of his sister.

There’s a 26-year-old kid in North Dakota who started working on heavy equipment and within six months he’s making $130,000 a year. He quits his job because he can do better freelancing on the high plains working on heavy equipment. The story is incredible because he’s married, second kid on the way, zero debt and just bought a house in cash. He learned a skilled trade, went to the place where the opportunities are greatest, and applied his skill. Guys like that should be on a poster, whether it’s about the auto industry or the construction industry.

Companies that are on the front line of recruiting skilled labor, in my humble opinion, need to make a more persuasive case for the opportunities that actually exist.

Daniel Lai is a communications specialist and copywriter at the Detroit Regional Chamber.